Markdown is simple in general. Over the years, however, I have observed two things that are surprisingly hard and many people have stumbled over them, including experts in my eyes.

1. How to write verbatim content, especially text that contains three backticks

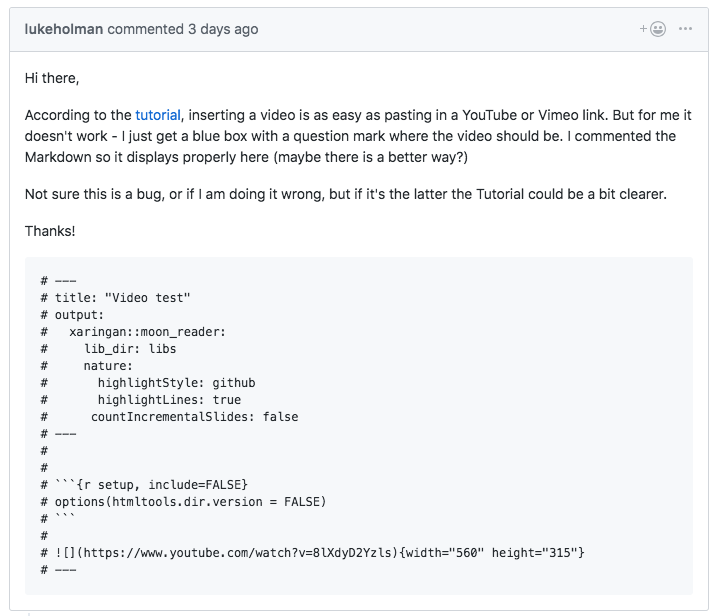

This is the thing that tortures me weekly, if not daily, because without knowing how to write verbatim text, the Markdown output will be poorly formatted. It is not rare for me to see GitHub issues like this:

Despite of the fact that I have explicitly mentioned in the GitHub issue template how to write verbatim text and I have also given an example, some users still fail to do this correctly. With dozens of other GitHub issues to deal with, I hope they could forgive me skipping issues like this. I don’t mean to blame users like this one. Obviously they have read the issue template—the above user said in the GitHub issue:

Hoping I have all the backticks right in this example.

It is just that this Markdown syntax is too hard to understand:

-

To write text verbatim, use three backticks to wrap the text.

``` verbatim text here more verbatim text ``` -

To write verbatim text that contains three backticks, you have to use four backticks to wrap the text.

```` a normal paragraph ``` verbatim text here more verbatim text ``` ````

In general, you need at least N+1 backticks to write N backticks verbatim. As an exercise, now you may ask yourself what you should do if your text contains four backticks, or five, or six. Note that instead of using N+1 backticks, you could also indent the text, but it can be tricky to determine how many spaces you need in some cases.

I didn’t fully realize how hard this “simple” rule was until I saw R experts like JD Long failed to provide a reprex in plain text a few weeks ago because it contained three backticks. He chose to post a screenshot of the text. I almost jumped off my chair and killed him when I saw the screenshot. At that moment, I realized I should give it up, and accept the fact that this is just surprisingly hard for most Markdown users. Okay, I’ll just bite the bullet and edit all your poorly formatted GitHub issues if I have time.

Below is one more common example of what users do when they don’t know how to format text containing three backticks. I could give many, many more examples like this. Again, the point is not to complain about these users, but show how hard it is for users to know the right syntax.

BTW, I want to thank Marcel Schilling one more time for helping me reply GitHub issues (it is so great to have someone in an earlier timezone to help). You have made indirect yet important contributions to my other open source projects.

The reason for this issue to occur frequently in the R Markdown world is that R Markdown documents often contain three backticks (for code chunks). They also often contain three dashes intended for the YAML frontmatter, which happens to be the syntax for the second-level section headers, and you certainly don’t want this to be displayed as a section header:

---

output: powerpoint_presentation

---

2. Nest child elements properly in a list

The second hard thing about Markdown doesn’t appear frequently, but from the examples I have seen, few people really got it. That is, how to write elements other than bullets within a bullet list. In most cases, the answer is simple: you need to indent these elements. For example, if a bullet item has three paragraphs, the second and third paragraphs have to be indented, e.g.,

- One bullet.

With one more paragraph.

And another paragraph.

- Another bullet.

> A quote.

1. Or a numbered list.

2. Number two.

The actual rules are actually fairly complicated. Again, you have to read the Pandoc manual for the precise syntax. Note that I’m talking about Pandoc 2.x here. The rules were different in Pandoc 1.x.

BTW, there is one lesser-known rule for numbered lists. That is, you don’t have to use the incremental numbers 1., 2., …, N.. None of the numbers except the first one matter. Any numbers will work, which can be surprising. For example, the following examples all produce the same list:

1. One

2. Two

3. Three

1. One

3. Two

2. Three

1. One

9. Two

5. Three

Only the first number determines the starting number (it doesn’t have to be 1). The rest of numbers will be ignored. For people who care about the cleanness of their GIT history (like me), you can always use 1. as the prefix, so your GIT history can be absolutely clean when you reorder items in a numbered list or add/delete items.

1. One

1. Two

1. Three

If you have child elements in a numbered list, you also have to indent them, otherwise the output can be unexpected. As an exercise, guess what the following Markdown source produce:

1. One

More on one.

1. Two

Explaining two.

1. Three

Now you may call me liar since I have been telling you that Markdown is simple.