“Hey Yihui, quick question for you…” For many times I have been asked “quick questions” on Twitter, on Slack, or in emails. I do love questions that are quick, because the net gain can be significant: you won’t need to spend hours on questions of which the answers are obvious to me.

Most of time I reply to such questions within seconds after I see them, and some people have been surprised by how quickly I respond. The only problem is, those questions are not always quick. This can be particularly problematic when I’m reading messages in IM (instant messaging) tools such as Twitter and Slack, because I usually don’t intend to stay in IM tools for long. I often open Slack only once every morning to check messages from yesterday, and quit it for the rest of the day. I have installed a Chrome extension to limit my Twitter time to 10 minutes per day. When quick questions do not really seem to be quick, I feel I’ll be stuck there. Should I continue to ask for more information (which can lead to several rounds of asking), or simply ignore the question? I don’t know.

In general, I’m not big fan of IM tools, although I’m not truly against them. They are convenient indeed. For example, you can ask a friend for dinner together via a text message. That is totally cool. However, if you have something important to say, it is probably not a good idea to bury it in the endless and chaotic stream of messages. For example, I never believe it is a good idea to debate on anything on Twitter.

The possibility of your questions being unintentionally overlooked is one problem. The other problem is, by asking a quick question, you probably won’t have a chance to think hard enough about the question or try a little bit to find the answer first. As a result, the question could be unclear, or due to a simple mistake. If you make a little bit more effort, you might just discover the answer by yourself.

With apologies to Carl Boettiger, I want to use a quick question he asked me on Twitter today as an example to show the possibility of answering your own quick question:

@xieyihui stupid question for you: how can I put literal TeX into Rmd these days? I thought that just worked but pandoc (v2.1.1) seems to be auto-escaping stuff like

\begin{tcolorbox}

I was surprised by this issue because that did not sound like what Pandoc would do. I mean Pandoc has supported raw LaTeX content in Markdown for years. I had a guess about how this could happen (special LaTeX characters that are not properly escaped in tcolorbox), but without seeing a reproducible example, it was hard for me to know if my guess was correct, which means I had to ask for more information. Then this wouldn’t be a “quick question”. Instead of guessing and asking back and forth, I recommended him to file an issue with a reproducible example to the rmarkdown repo on GitHub. A GitHub issue would certainly be better than a tweet in this case: it is hard to provide a self-contained reproducible example in a tweet due to the arbitrary 280-character limit.

Guess what? Then he just quickly realized what was wrong by himself. Had he tried to make a small reproducible example, he would not need to ask the question at all. Had I seen a reproducible example, I’d probably notice the problem within seconds, too. The problem was just that the quick question contained too little information. When one has to start asking for more information or clarification, the quick question is no longer quick.

I don’t mean to discourage people from asking me quick questions. I just want to set your expectation correctly: when I don’t answer a question on Twitter, it probably means it is not clear to me, and you may try to ask a slow version of the question on RStudio Community or Stack Overflow or other places that don’t have the length limit, providing as much information as you can. If you need convincing examples, you may take a look at Daniel Anderson’s experience (he almost wanted to ask on Twitter but decided to go with Stack Overflow instead, and succeeded), or Richard D. Morey’s, or Vidhya Kalaichelvan’s.

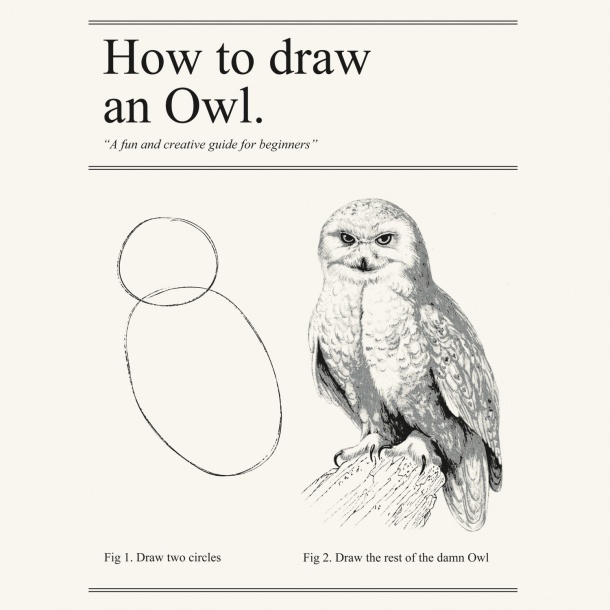

Remember, the quick question might be like the two circles in the guide below on how to draw an owl, and the real question might be the owl on the right. Are you absolutely sure I can answer your question after seeing the two cirles?